Download our guide here: The Castor Roman Trail Guide

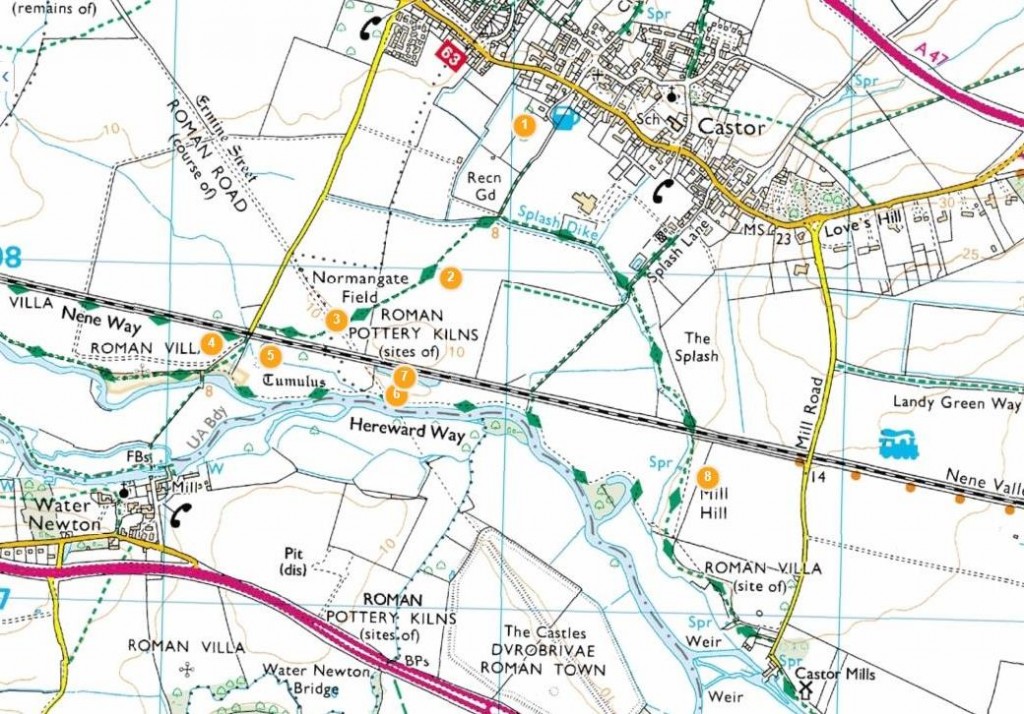

Welcome to the ‘Route Plan’ and teachers notes for the Castor Roman Walk. The walk is approximately 3km, with an optional extension of 0.7km. We suggest that you bring with you OS Explorer 227. The start point is at grid reference TL 124984

This is very largely a walk of the imagination, but what imagination!

This is very largely a walk of the imagination, but what imagination!

- Roman Emperors travelled across the fields that you will cross;

- Roman Legions tramped the roads you will stand on, heading to Hadrian’s Wall;

- In the fields where wheat now grows, potters made Castorware that was extensively traded across the province. (and further afield?)

- The large Roman building, or Praetorium, where St Kyneburgha’s Church now stands was as big as Peterborough Cathedral

- And near to where you walk the oldest known Christian silverware in the Roman Empire (now in the British Museum) was found.

But you will need your imagination and a sharp eye for the evidence in the landscape to tell the story, as the evidence of Roman occupation of the area is very largely buried.

Starting the Walk

The walk starts where Church Walk meets Peterborough Road, at the corner of the school playing field. Turn right and walk down Peterborough Road, past the Village Hall and take the first left into Port Lane opposite the Prince of Wales Feathers. Go down Port Lane and stop when you have passed the right angle bends after the houses.

1. Berrystead Manor

On the right, at the far side of the field, is the site of Berrystead Manor, which was occupied from the Saxon period onwards, and is one of the earliest known post-Roman settlements in the area. The manor would have been a substantial farmhouse, surrounded by a moat. You can also see evidence of ridge and furrow cultivation in the field immediately in front of you. This is evidence of Saxon and medieval strip farming

Directions to next point:

Go on to the end of the path past the cricket field on your right, turn right and after crossing the dyke, take the path diagonally across Normangate Field. Walk across the field, and stop about half way to the hedge.

2. Normangate Field

You are now standing on the site of one of the largest industrial estates in Roman Britain. There would have been pottery kilns, iron works, blacksmiths, leather workers, and workshops for all the trades needed to supply a major town and the Roman army. There was a network of small roads with workshops, houses and even Temples clustered around them. Most of the industry was placed outside Durobrivae (which is on the other side of the river) because of the smoke, noise and smells it would have created.

You are now standing on the site of one of the largest industrial estates in Roman Britain. There would have been pottery kilns, iron works, blacksmiths, leather workers, and workshops for all the trades needed to supply a major town and the Roman army. There was a network of small roads with workshops, houses and even Temples clustered around them. Most of the industry was placed outside Durobrivae (which is on the other side of the river) because of the smoke, noise and smells it would have created.

Directions to next point:

After walking through the hedge you will see a slight rise in front of you. Stop on top of the rise. On your right you will see two trees in the hedgerow on the other side of the field; on your left you will see a wooden electricity pole in the next field. The line of Ermine Street passes between the two trees and if they, you and the pole are in a straight line, you are standing on Ermine Street.

3. Ermine Street

Ermine Street, was the Roman road from London (Londinium) to York (Eboracum), and in many places our modern roads still follow the Roman’s route. You can see the mound that is the remains of the Roman road, the low mound where earth has piled up over the remains of the road as a result of modern ploughing. You are standing in the footsteps of Emperors. This would have been the road taken by Emperor Hadrian when going north to supervise the work on the wall named after him; Emperors Constantine, Septimus Severus also would have traveller this way, the main north-south route in Britain, as would Governor Agricola. It was not just a royal road, it was a busy thoroughfare, with carts and pack animals moving trade goods; Roman Legions moving to new postings, with their baggage trains and their families following behind; and local people going to market or visiting their friends.

In this area a stone coffin was discovered in the 1970’s after a farmer hit it with his plough. It contained the body of a wealthy woman who must have been connected to the industry in the area, as she was buried with gold and jewellery and a flagon containing food for her journey to the afterlife.

Directions to next point:

Follow the path along the field edge on your right to the bottom of Station Road, and cross the railway. Please take care as trains use this line at all times, not only at weekends. Immediately after crossing the railway look across the field on your right towards the large electricity pylons on the horizon.

4. Roman Villas

In this field Edmund Artis excavated the remains of a Roman villa in the 1820’s (see plate). The sites of several villas or large farmhouses are clustered around Durobrivae. They were the home of wealthy landowners or industrialists who owned factories and workshops and wished to escape the bustle and noise of the town. Some of the villas had the luxury of mosaic floors and under floor heating systems.

Directions to next point:

Return to the path, move down to the river and turn left, crossing a small footbridge. 40 metres into this field, on your left about 75 metres away, you will see a low mound. Please note that there may be livestock in this and the next fields. They are generally used to walkers, joggers and cyclists going through their field and take no notice of them.

This is the remains of a Bronze Age barrow, or burial mound, which pre-dates the Romans by hundreds of years.

5. Bronze Age Barrow

This is the remains of a Bronze Age barrow, or burial mound, which pre-dates the Romans by hundreds of years. Bronze age people commonly buried their dead in such mounds, often with grave goods such as weapons and jewellery. We should remember there is much evidence of human occupation in the landscape long before (and after) the Romans arrived.

Directions to next point:

Now follow the river to the other end of the field. Cross the little bridge into the next field. Please note that it may be wet and muddy underfoot at this point. Turn left to the top of the rise, (you may need to move a few yards into the field to avoid the stinging nettles), where you will find:

6. Site of the River Bridge

This is the point at which the Romans crossed the river by means of a bridge. This would have been a wooden structure on stone piers. We know that Ermine Street crossed the River Nene at this point, both from aerial photos of crop marks, and also as the piers were discovered in the 1920’s when the river was dredged. On the other side of the river the road ran across two small fields, past the site of a Roman fort and entered the town of Durobrivae through its north gate.

Roman Fort

Looking over the river, behind the hedge at the back of the field, on the higher ground, was a Roman fort. It was smaller than the Longthorpe fort, about 2 hectares in size, and was constructed from wooden palisades behind the three defensive ditches that are clearly seen on aerial photographs. It could accommodate about 600 men whose task was to protect the river crossing, but it may have been occupied for a relatively short period before the Roman army moved north.

Durobrivae

Durobrivae was a small Roman town covering some 18 hectares, straddling Ermine Street. It is largely unexcavated but was an important trading centre and stopping-place on Ermine Street.

7. St Coneybeare’s Way

Look back towards Castor over Normangate field, the site of the industrial estate. On your right, you will see an old, gnarled pollarded willow tree. Between this and the electricity pole, at the top of the slope running down towards the railway you can see a rough layer of large stones, with smaller stones underneath.

Look back towards Castor over Normangate field, the site of the industrial estate. On your right, you will see an old, gnarled pollarded willow tree. Between this and the electricity pole, at the top of the slope running down towards the railway you can see a rough layer of large stones, with smaller stones underneath.

Here you can see remains of a cross-section of a Roman road. (See photo) This is St Coneybeare’s Way which ran from the river crossing, branching in the field, one branch heading to the Roman buildings surrounding St Kyneburgha’s church, the other heading eastwards towards Longthorpe. The cross section shows clear evidence of how Roman roads were constructed.

8. St Kyneburgha Church

Walk on down the river to the next hedge, turn left under the railway bridge and walk straight ahead until you reach Peterborough Road (approx. 1km), turn left and walk back to your starting point at Church Walk.

Explore the Church and the area around the church Walk around the churchyard and church hill.

Stop at the bottom of church walk and look up towards the church.

You are now looking at the site of a large Roman building or ‘Praetorium’ that was situated on top of the hill just behind the church. There were other roman buildings here as well. Just where you are standing, on the corner of the school

field, there was a substantial roman bathhouse with a hypocaust or underfloor heating system. Look at the illustration of the excavation made by Artis of the same site. His discovery has since been confirmed by a recent ‘Time Team’ excavation.

Go up the path to the church and walk around the outside of the building.

The church itself was built around 1120 but is on the site of a Saxon convent founded by St Kyneburgha which in turn was built amid the ruins of the Roman Praetorium. As you go round look for the thin orange coloured tiles and bricks in the walls. These are all pieces of roman building material such as ‘pilae’ or bricks from the piers of heating systems and fragments of ‘tegulae’ or roof tiles, that have been was re-used in the walls of the church. In the rear walls of the church you can also see what look like round bricks. These are parts of small roman columns that have been cut up and used in the walls.

Inside the church itself you will find a roman altar in the north aisle. This had been re-used by the Saxons, but is typical of the sort of domestic altar that a roman family might have used to make offerings to their household gods.

There are many other interesting things in the church –look at the leaflets that will tell you more on the Saxon history of the site.

The Praetorium

Coming out of the church turn left

You will see the grave of Edmund Artis, our famous early archaeologist who did so much to discover the roman remains in this area in the nineteenth century.

Continue to walk along the path to a gate that brings you out onto Stocks hill.

On the other side of the road you will see two large clumps of old stonework emerging from the wall. These are the remains of the roman foundations of the Praetorium built in the ‘herringbone’ style.

Carry on up to the crossroads and pause at the crossroads.

Look at the map of the area around the church. You are now on the site of the Praetorium, one of the largest buildings in Roman Britain that stood on top of the hill just behind where the church is. It was a single building over 110metres

wide and 20metres deep with a central range and two wings that faced down the hill. By the size of the foundations we can tell that it was three stories high at least. It had many different rooms, some with mosaic floors one of which extended into the churchyard and was first excavated and drawn by Artis and then rediscovered by ‘Time team’. Despite its size and importance we are still not sure who lived in it or what its purpose was. Our best guess is that it was the residence and headquarters of an important roman official who may have been responsible for a large area to the east in the fenland which was an imperial estate. His job would have been to administer that estate and ensure that all the profits were retained for its owner –the emperor.

Optional Walk Extension:

Before you reach the oxbow look to your right over the river, and you will see at the back of the first field on the other side, a row of trees, and behind them an earth bank. This is the site of the town of Durobrivae, and by tracing the trees and bank round you can follow the north and west walls of the town. Its southern wall runs along the line of the A1, a very obvious feature of the modern landscape. This was a very busy town that developed over a number of years, as the street pattern is clearly random, and not on a gridiron as the planned Roman towns were. It was a busy town, with shops and stalls lining the streets, a mansio (tavern), temples and a market place. You will get similar views as you climb Mill Hill after crossing Splash dyke by the little bridge. 9. You are standing on the site of another villa excavated by Artis, in which a mosaic floor was found. Many villas were the centre of large agricultural estates, and as well as living accommodation for the landowner, was surrounded by stables, byres, barns and other farm buildings.

From here, look back over your walk from the top of Mill Hill, and compare it with the same scene, sketched nearly 200 years ago by Artis. What has changed? What has stayed the same?

Do not cross back over the dyke, but walk towards the railway and cross the style by the railway bridge. Follow the dyke under the bridge and through the next field, turning right onto the track when you leave the field, and keep going straight on until you come to Peterborough Road, turn left and walk back to your starting point at Church Walk.